The platform

Dobsonian telescopes ("Dobsonians") were popularized by San Francisco astronomer John Dobson in the 1970s. A Dobsonian consists of a Newtonian telescope (with a large parabolic primary mirror and a small and flat secondary mirror) riding on a simple altazimuth base. It usually has no built-in motors to track objects in the sky. Everything is reduced to a minimum with the only expensive part being the primary mirror.

If an observer wants to follow heavenly objects, he / she has to push or pull the dobsonian telescope. If low magnifications (below 150x) are applied, pushing or pulling the telescope is no problem. But for observing at high magnification (above 150x), moving the telescope manually can be very cumbersome. As a planetary observer, I often use magnifications of 350x-450x (moon, planets) and up to 1200x (double stars).

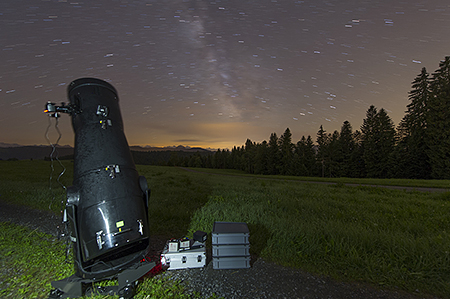

Tom Osypowski from equatorialplatforms.com produces equatorial platforms which are placed beneath almost any dobsonian telescope and track objects in the sky for about 80-85 minutes. After a short reset, the platform tracks for another 80-85 minutes and so on. The platforms are custom-made. Depending on the latitude of the observer, the weight of the dobsonian telescope, the position of its center of gravity and the dimensions of the rocker box, the platform will have a different geometry (though an existing platform can be adopted to carry different telescopes).

In April 2010, I contacted Tom Osypowski by mail. I was fascinated by the images on his website taken through dobsonian telescopes on equatorial platforms and by the observing reports. Tom replied to my mail on the same night but it wasn't until mid October 2010 that I decided to order one of his dual-axis aluminum platforms after trying to observe Jupiter at 350x for a couple of hours on different nights.

Will the platform have an impact on the stability of the dobsonian telescope? Will it track accurately enough for high magnifications? Will it take a lot of time to get ready for observing? Will it add a lot of complexity to a beautifully simple system? These were some of the things I was worrying about. I trusted the advertisement on Tom's website. The images of the moon and the planets and especially of deep sky objects were just too tempting.

In December 2010 - much earlier than anticipated, a huge box with the equatorial platform arrived (the biggest and heaviest box I've ever received in my life). "Wow, that platform looks awesome" was my first thought. This was my very first encounter with an equatorial platform. What a piece of exquisite craftmanship.

In January, I put the platform to a first test. On the very first night my 16" f/5 dobsonian followed the planets and stars. No vibrations at all, not even at 1000x-1200x when looking at the multiple star Almanach (Gamma Andromedae) and other double stars. The dobsonian was as stable as without the platform and tracked as perfectly as any equatorial mount at the highest powers. What a walk in the park! During the following nights, I've observed more and more objects and was impressed by how well the platform performed at very high powers.

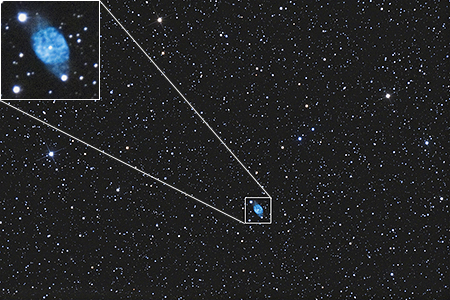

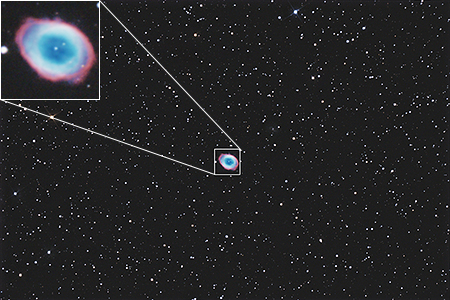

How about astrophotography? After a few weeks, I've organized an off-axis guiding system, an autoguider, and a coma corrector. In April, my Canon 20Da had a "first light" through the 16" f/5 dobsonian. The results of my first astrophotography attempts can be seen below.

I faced some challenges during the first few months of imaging. The challenges didn't concern the equatorial platform but the pitfalls of astrophotography:

- A faulty position of the pick-off prism of the off-axis system caused some vignetting in the first batch of images.

- It took me some time to figure out the best settings of my DSLR camera. I worked with too high ISO values (ISO 1600) and too long exposure times (10 - 15 minutes). These settings led to washed-out star colors and blown-out highlights and all kinds of noise (banding, pattern noise). After a year I started to dial down the ISO value to 800 and restricted the exposure time to 3-5 minutes (settings for the Canon 20Da and the Canon 450Da) with better results.

- The light shroud of the dobsonian telescope blocked part of the light path and caused diffraction effects on bright stars.

- My first DSLR (Canon 20Da) suffered from purple amp glow in the image corners. It wasn't until I switched to the Canon 450Da that these problems fully disappeared.

- Vignetting of the camera body and the optical elements caused some problems, especially with post-processing of extended deep sky objects. After a few years, I purchased a flat field panel for the 16-inch telescope, making post-processing easier.

- Centering an astronomical object in the camera viewfinder proved a bit more difficult than anticipated. Even though the object appeared in the center of the viewfinder, it turned out somewhere else in the final image: It is rather difficult to judge whether an object is perfectly centered in the viewfinder in darkness. It wasn't until I started to use an eyepiece with illuminated crosshairs to center an astronomical object (prior to attaching the camera) that these problems vanished.

I reprocessed the first images from the years 2011 and 2012 - which were taken under the circumstances described above (see images on this page) - in 2020. I leave them on the website mainly for nostalgic reasons.

Since 2013, I've been working with a Canon 450Da camera and a new telescope, a 16-inch f/4.5 "Ninja" dobsonian sold by Kasai Trading (unfortunately, the Ninja telescopes are not produced anymore). The closed tube and the excellent weight balance convinced me to switch. Tom's platform now carries the Ninja. No changes to the platform were necessary. My current work with the Canon 450Da and the new Ninja telescope on the equatorial platform can be found here and here .

Astrophotography combines two exciting disciplines - astronomy and photography. If everything works out as planned, it can be very thrilling and satisfying. It's a multi-step procedure from the point when you have decided to drive up a mountain for an astrophotography session to the point when the image of a remote galaxy is on the memory card. If any of those steps fail(s), there will be most likely no astrophotography during that night. A missing or broken cable, a missing or broken or loose screw, a decollimated optical element, dew on an optical element, low batteries, a short circuit, a missing memory card, a cute little fox or a variety of other things can ruin the night.

I did astrophotography with roll film and a 10" f/6 reflector on a German equatorial mount back in the 1980s. It was challenging back then and I feared it would get even more difficult with the platform. So how about astrophotography with the platform? In short, it's as easy or difficult as with a "normal" German equatorial mount. After arriving at the observing site, it takes me about one hour to set up and align the platform with a bubble level and the polar finder, put together the telescope, collimate the optics, connect all cables, reset the platform for an 85-minute guiding session, search for the first object, focus the camera and autoguider and find a guiding star and push the remote release. If anything goes wrong, it will take more time. Since the primary mirror needs to cool down for at least one hour, I don't see this as a restriction.

There are things which are easier with the platform: E.g. it's much easier to balance the dobsonian telescope on the platform. And it will stay balanced during the exposure. Balancing a big Newtonian telescope on a German equatorial mount can be very difficult and during the guiding process, the torque changes. On the other hand, wind is the enemy of the dobsonian on the equatorial platform. If there is wind, it can ruin the guiding quite easily. I work at focal lengths of 81" (Ninja) and 90" (Zambuto), so the guiding needs to be extremely precise (note: the TeleVue coma corrector slightly increases the focal length of the 16" primary mirror).

Astrophotography is a demanding task but the results are rewarding and exciting. I've always felt it's worth the efforts. I probably could get more resolution out of a 16" mirror by putting it into a solid tube and onto a heavy-duty German equatorial mount. But such a mount would be very expensive (costing at least three or four times as much as the platform) and it wouldn't be a mobile solution anymore. I feel the equatorial platform is one of the most important innovations in amateur astronomy since the invention of the dobsonian telescope. It doesn't make the good old German equatorial mount obsolete but it turns a simple dobsonian telescope on an altazimuth mount into a fully fledged observatory with exciting capabilities. I've mainly ordered the platform for observing. I love to sketch at the telescope and without the tracking capabilities things get difficult. Now I can even take pictures with the telescope.

Continue reading: Part II: The guiding / imaging setup